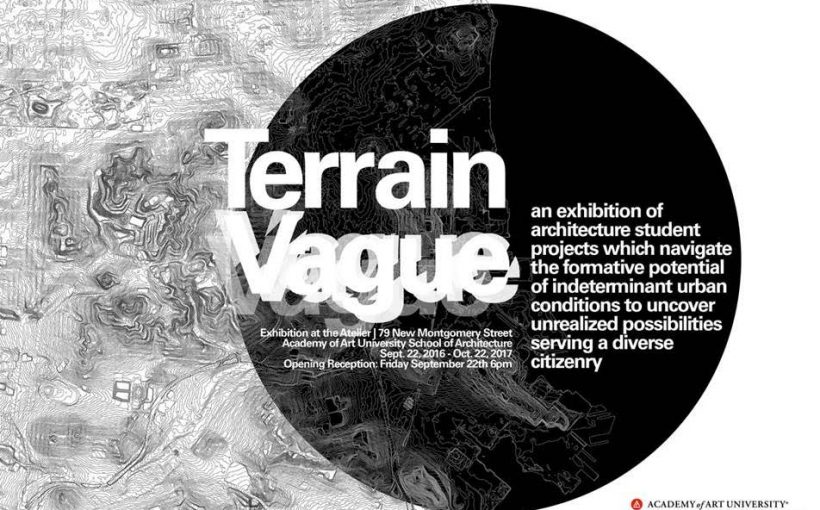

Terrain Vague: The Space of the Possible

It is difficult to discern whether or not Ignasi Sola de Morales coined the term, “terrain vague” to refer to the spatial detritus of cities, but we do continue to credit him. We credit him, in part, because his essay, in which the term appears, marks the entry of the term into regular use by those in architecture, landscape architecture and urban design. “Terrain vague,” he wrote, can be seen in “the relationship between the absence of use, of activity, and the sense of freedom, of expectancy, …void then as absence, and yet also as promise, as encounter, as the space of the possible.” When Sola de Morales’ essay first appeared in 1995, architectural and urban discourse was enamored of the possibility “terrain vague” offered as a kind of “third term” for urbanism. Terrain vague was a recognition of an urban non-place – the leftover spaces of parking lots and underpasses, empty lots, unusable real estate, an endless skyline of low-profile suburbs, miles of office parks – any place really that did not possess the characteristics of a “place.” Terrain vague sounded, well, vague, undefined, a space of the possible. Terrain vague was an urban “other,” and even better, it was right under our noses.

Academies of architecture and urban design have since gravitated to the idea of terrain vague as a perfect pedagogical challenge to their maturing students: the problem of how to seize on the space of the possible, and then, how to make design on a terrain without overriding the poetic of its vague… In other words, is that which makes empty lots and storehouses and fields of undifferentiated parking and unoccupiable harbors and even the ticky-tacky of suburbia “vague,” a set of qualities that can be preserved in design, or does design ultimately eliminate vague-ness? Furthermore, is terrain vague the outright sign of an informal, small-a architectural, urban vernacular, and if so, how does design work outside of the master or dominant paradigms of capital-A Architecture to embrace the bottom-up, the popular, and the “undesigned”? Any student of design who can navigate these territories between high/low, formal/informal, top-down/bottom-up, successfully or not, is seen as more prepared to face real world challenges. Terrain vague is therefore a common studio assignment across the United States.

To see these models and projects in the context of this gallery, we move conceptually as the student once did – between the complex irreverence of the urban mess and the precision of the design. We call upon the student to navigate social and typological disparities, to respond to the needs of public space, to use design as a means to resolve problems of social inequality; and we ask them to do so with attention, rigor and determination. We ask them to make buildings that do not merely react to global urban conditions, but are proactive cultural knitters: deploying techniques as a toolkit for consciousness, bridging gaps, revealing, binding. It’s a big ask.

Student effort is not the sum of its parts, it is an open-ended search, and deserves to be celebrated as such. As the graphic for this exhibition suggests, Terrain Vague is a moving target – a dot of perception more or less zeroed in on a shifting territory – moments of clarity among fields and flows, hills, streets, houses, alleys, underpasses and parking lots, …the production of the sign, “You Are Here.” Displayed together, the here-you-are-in takes in the entirety of an urban world – its’ publics, its’ deep social rifts, its’ multiple existences – and attempts to translate these worlds into the life of buildings – their practical uses, their articulate tectonics, their deep cultural meanings. The student could respond facilely, superficially – with an artful composition of forms that might be visually satisfying. Instead, they give us the mess that they perceive, they go deep, they reveal and tease out the hiddenness of our cities. And, it is this deep perception they bring to their design work.

If the city is, at all times, not The City, so much as multiple “cities,” then we must recognize that any one city is a kind of secret, waiting to be revealed to vision. Italo Calvino had promised us, fictionally or not, that any city was made up of thousands of potential “Invisible Cities.” Terrain vague offers to us the hope that urban identity is so much more than one city – and throughout, the students are tasked with fulfilling all that architecture is truly capable of in a complex, global, diverse world, “of freedom and expectancy.” . We are gendered, ethnic, aged. We experience our cities according to a polyglot of food, transit, friends, followers, hashtags, spaces and places. Deep studio and thesis work is beautifully imperfect, striking in moments, optimistic and daring. Like the lived city, the works seen here open, interrogate, engage the many lives, many cities, promises, and encounters, “the spaces of the possible” …terrain vague indeed.

Dora Epstein Jones

For further reading:

Ignasi Sola de Morales, “Terrain Vague,” in Anyplace, ed. C. Davidson (Cambridge, MIT Press, 1995).

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (New York, Harcourt Brace, 1978).